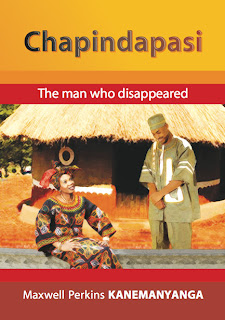

Book:

CHAPINDAPASI

Author:

Maxwell Perkins Kanemanyanga

Reviewer:

Raphael Mokoena

This is the

third published collection of stories by Maxwell Perkins Kanemanyanga. It is

reassuring that he has not rested on his laurels, and continues to be creative

as a writer.

Reading his

new book, one wonders when Kanemanyanga will write/publish his first novel.

This is because his short stories often bear the germs and suggestion that they

can be converted into even longer fiction; if the author so desires. This is

obvious from his latest collection.

Let us start

with the title story, CHAPINDAPASI.

From the very beginning we can see that rural, ancestral Africa is being

re-created here, with references to “huts” and all-powerful Kings. We learn

that King Makombe is a ruthless, cruel leader, who even ensures that anytime

his many (12, 13, 14…) wives, bear male children, such are killed!

He is an

absolute monarch and polygamist, blood-thirsty too. War and death stalk his

reign “no one was allowed to keep baby boys”. Did this make him feel

invincible? The King marries a young lady Tikidi, who outwits him, ensuring

that her own baby son is not killed upon birth.

Inevitably,

the king gets older and we can see real pathos as he states:

“Most people

think I am a strong, tough king, a warrior, but I am a foolish man. I killed

all my sons, I thought I would live for ever, but here I am weeping like a boy

sitting on top of the graves of my sons I killed,” (Page 18)

Then he

learns that he does have a surviving son!

Yet in this

new collection, Kanemanyanga’s frequent unconvincing endings’ continues. In

Chapindapasi, the conclusion is melodramatic and does not flow; it is as if the

author wants to force the title of the story (and the book) – The man who

Disappeared – into the story at all costs.

Kanemanyanga

writes in a fairly simple, flowing, competent manner. But again, another aspect of his writings – the

suggestions of unnecessary cruelty and sadism – continue in this latest work.

The short story, Love and Betrayal

displays this.

The

protagonist here, Maidei, the young “leggy, skinny dark beauty” spends all her

youth being hopelessly in love with David, at best an unworthy suitor. Maidei’s constant, steadfast love – she even

travels from Zimabwe to SA all in a bid to be reconciled with an ungrateful

David – is unrequited. Yes, readers can see that David has an inferiority

complex mingled with frustration, but he is a bad person in essence.

David’s

reaction to Maidei when she meets him in South Africa for the first time is

crude and rude, with the narrator seemingly sharing this approach: “By now he

was angry…he could not believe she was talking such shit” (Page 33)

Maidei gets

pregnant by the same David, and his reaction is inhumane and brutal yet again.

He parts with her and leaves her to suffer on. Why should the young lady go

through all this, including being ostracized by her own parents’ Suddenly, much

later on David has a change of heart and is ready to apologise and turn over a

new leaf; and be with her permanently.

It is almost

inevitable that at the end – despite the fact that David is apparently a

changed man and travelling back to the wonderful young lady – he loses his life

in a tragic accident. So Maidei’s sufferings continue needlessly, a selfless,

idealistic lady and mother, loses all. One cannot but feel that this conclusion

rather ruins this story.

The other

stories generally continue in the same vein – especially Flames of Fury. The long-suffering Mama Melody’s plight, which

reaches a peak with her horrific fiery death, appears to be unnecessary too, as

the man who has wronged her so badly is also on his way to her to apologise and

become a much better partner!

This is

another finely written collection of stories authored by Maxwell Kanemanyanga,

but one cannot help but wonder whether there is any real need for the frequent,

gratuitous sufferings, tragedies, and pathos he churns out?